Individuality in Readers of the Work of Art: The Reader of Visual Art

See more academic essays

In the previous pages I have analyzed pieces of literature using ideas formed to serve the needs of literature. Favoring the power of the reader over that of the author, I do not submit to a belief in authorial intention. In the following pages, I will apply the idea of reader involvement and multiplicity of the text to works of visual art. I intend to show how the interaction between individual readers and works of visual art enriches an understanding of art's possibilities while allowing an infinity of meanings to emerge.

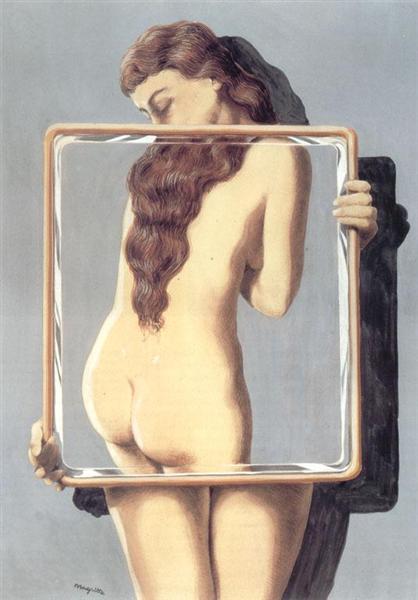

Consider this painting by René Magritte, for example. In the painting, the female is fragmented by the placement of a mirror which she holds before her. The image in the center mirror is awkward and stiff. I cannot get a full view of the woman, who is hiding behind the mirror. A tuft of pubic hair pokes out from the bottom edge of the mirror. My instincts tell me this is an ugly image; I do not like the indiscreet pubic hair, the protruding backside of the woman, the flat, dark streaks of hair. On a first reading, my thoughts remain on the level of like and don't like.

Formerly with the collection of Galerie Octave Negru, Paris.

Illus. 30 of This Is not a Pipe, by Michel Foucault, trans. and ed. by James Harkness (Berkeley: U. of Ca. Press, 1983).

For many art historians and feminists, such fragmentation of the female image has sexist implications. In the words of Mary Ann Caws, "When a fragmented image is said to represent us, as we are supposed to represent woman, we may either refuse such synecdochic enterprises of representation or demand, if not totalization of the model, then at least reintegration, according to terms both private and public" (272). Caws see Magritte's image as a negative one because it interrupts the potential beauty of the image. In her analysis, a work is the deserved target of the female demand for reintegration when it violates the integrity of an image of woman (representing all women). Caws takes issue with Magritte's painting because it "makes no room for pride -- only heavy astonishment at there being no frontal state to observe . . ." (274). The painting is not satisfactory because "we are always shut out" (274).

Caws' comment expresses common indignation with Surrealist representation of women. Surrealism produced a plethora of images inspecting, distorting, tearing apart, and metaphorically molesting the female body, and depictions of female sexuality often went hand in hand with depictions of violence. Susan Suleiman, in her discussion of Rosalind Krauss's The Originality of the Avante-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, asserts that "Krauss's brilliant discussion of Surrealist 'optical assaults on the body' (p. 70) elides the difference between the subject who is the agent of the assault (and who is almost invariably a male photographer) and the object that is the target of the 'active aggressive assault on reality' (p. 65), this object being almost invariable the female body" (Suleiman, Subversive Intent, 16). Caws' response, one that favors harmony over fragmentation, may seem a right response from a spectator whose gender is disserviced by the tactics of Surrealist representation.

Yet, on closer analysis, Caws' critique is problematic. In asserting that the good or natural female response demands wholeness in representations of women, Caws presents a narrow view of the spectator-art relationship. By demanding a reintegration of the image of woman, Caws is disallowing a multiplicity of interpretations. Her argument denies the possibility that a fragmented image of woman can mean anything other than pleasure for the male gaze. In other words, by imagining an idealized or over-delineated audience, Caws closes the work of art.

Magritte's Les Liaisons dangereuses has alternative readings. Surrealism was influenced by the Cubist desire to break away from naturalistic, perspectivally correct modes of representation. Magritte's Les Liaisons dangereuses, in addition to rendering awkwardness, makes me awkward; the double framing of the mirror inside the frame does not allow my eyes to rest squarely on a single figure. This restlessness is one of Surrealism's methods of unsettling the spectator. As Sidra Stich notes, the Surrealists "were intent on assaulting idealistic premises of harmony and order, which were blind to the realities of conflict and disorder . . ." (130).

At the same time, I notice other aspects of the painting. I see Magritte's Les Liaisons dangereuses as a commentary on, not a perpetuation of, the victimization of women by imagery. The body in the mirror is smaller and positioned differently than the figure holding the mirror. In noticing the differences between the two bodies, I become aware of the rift between real and represented. The awkwardness framed in Magritte's mirror speaks to me about the distortions inherent in representation and looking. My anxiety in looking highlights the problem: to represent is an awkward and at best only partially successful endeavor. Consequently, what Caws terms "the shame and difficulty of self-reading" is more valuable to me than a graceful, beauteous alternative. I find meaning in Magritte's painting through the instability and anxiety that it evokes. Rather than criticize Magritte's painting for denying the woman's privacy, as Caws does, I am intrigued and attracted by the issues -- privacy, representation, looking -- that I find in the work.

In addition, a consideration of the effects produced in audiences mitigates Modernist complaints about the lack of painting, of materiality, in the work of Magritte and other Surrealists. Admittedly, Magritte gives me much that is not new: he provides a representational painting, with recognizable images, a flat, two-dimensional surface, and evenly toned, unexceptional colors. I see a female nude, and call to mind the history of female representation: feminine desires are concealed, the body is turned toward the viewer's gaze. Magritte's smoothly painted realism leads me to believe that the image will be proportional and perfectly representational. My first impression, that the body-image is 'right-able,' is encouraged by the realistic drawing of the bodies. The turning point lies in my vague frustration that the body cannot be righted. As noted above, I find meaning in this very frustration. Thus, the paintings' less innovative elements -- representational imagery and academic painting -- make possible the twist on my expectations. If part of Les Liaisons dangereuses revolves around viewers' expectations concerning representation, then I forgive its literalness. Paradoxically, a painting might need to be familiar in order to be unfamiliar.

Again, involvement of the reader explains a vital part of the work of art. In Iser's notion of the gap-filling process we modify our perceptions and expectations as we read. A reader might find his or her ideas altered from one chapter of a novel to the next; reading is an experience over time. In the case of Les Liaisons dangereuses, my experience of it also continues over time. In the transition from one impression to another, I become aware of my own desire to reassemble the fragmented image, to get rid of the awkwardness. Repeated looking thus increases the personal nature the art-reader interaction, as the process of modifying one idea for another exists in countless permutations.

In addition, the self-consciousness encouraged by a painting like Les Liaisons dangereuses defeats the notion of 'convergence' toward a correct interpretation. By displacing expectations -- my instinctive need to be comfortable, to not feel awkward -- Magritte's painting draws attention to my normal habits of looking. The painting's emphasis on representation emphasizes the motion of reader-text give-and-take and helps me notice what I do in front of the image. Such an itinerary, contrary to Caws' demand for integration, prioritizes process rather than product. Consequently, I supress a desire for totality and allow myself to move through a second and third impression.

In sum, the perspective and creative movement of the spectator is a crucial aspect of the work of art. Caws' demand for wholeness suggests that we are to value identification with a painted character. Yet, I find it more fruitful to look at the interaction of reader to image and the meaning that arises. Rather than bemoan the lack of pride in feminine representation, I draw meaning from the very lack of graceful representation. The meanings I derive from Magritte's painting are connected to my own frustration with the image's "ugliness." Caws' demand for reintegration must be rejected in light of work that demands disintegration.

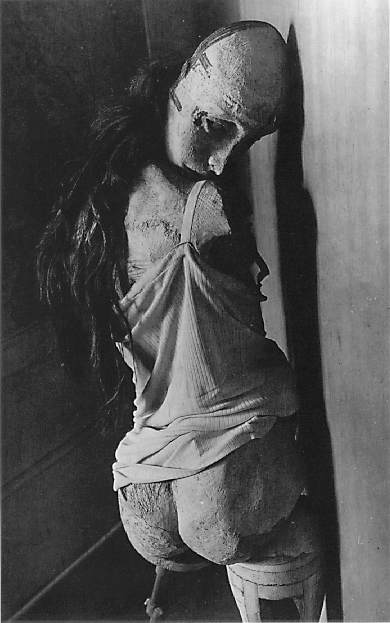

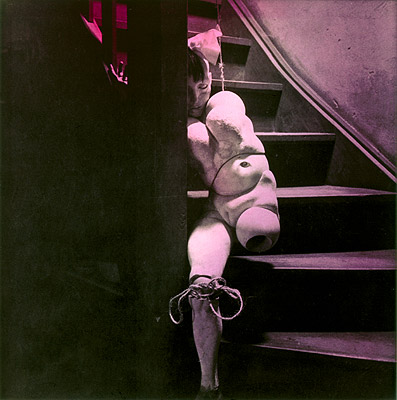

Another work from this period, La Poupée by Hans Bellmer (Fig. 2), illustrates this point in more extreme fashion. Angry responses to his work abound; writers vary enormously with respect to the value they assign his dolls. In the dialogue between Clayton Eshleman and Herbert Lust concerning Bellmer's La Poupée, Eshleman criticizes the dolls as "mental performance on the body of woman as if this performance had no social consequences (of rape, brutality, chopped-up bodies, gased corpses) . . ." (49). Similarly, Mary Ann Caws sees fragmentation of the female body in this case as a metaphoric act of violence: "What of a woman looking at an Other Woman clothed or caged, naked and yet neat and perhaps even integral, or dismembered like a doll of Hans Bellmer, untidily lying somewhere on some stair or floor. . .?" (269). Clayton's mentioning of "the body of woman" and Caws reference to "other Woman" suggest that it is the violence toward a generalized female image which is offensive.

Fig. 3. Hans Bellmer, La Poupée, 1935-36.

Gelatin silver print, 5.88 x 5.5 Collection of Timothy Baum.

Illus. 50 of Anxious Visions: Surrealist Art, by Sidra Stich (Berkeley:

University Art Museum, and New York: Abbeville Press, 1990).

Fig. 4. Hans Bellmer, Doll (La Poupée), 1934.

Gelatin silver print, 7.5 x 12 Virginia Lust Gallery, New York.

Illus. 49 of Anxious Visions: Surrealist Art, by Sidra Stich.

Fig. 5. Hans Bellmer, La Poupée (1935-36).

Painted aluminum, 24 x 7 Virginia Lust Gallery, New York.

Illus. 53 of Anxious Visions: Surrealist Art, by Sidra Stich.

Yet, looking at La Poupée from the point of view of a spectator, I get a different perspective. My initial impression is that Bellmer's dolls are intended to confront and disturb the spectator. When I look at the dolls, I cannot help but think of the words of André Breton, ". . .Surrealism aims quite simply at the total recovery of our psychic force by a means which is nothing other than the dizzying descent into ourselves . . ."(137). Given Surrealists' explicit desire to involve audiences, it seems impossible to do justice to Bellmer's work without looking at spectators' responses.

In this sense, the distress I feel when looking at La Poupée is part of what make the dolls interesting. Bellmer's dolls cannot be placed right-side up. The effect of the mismatching of body parts is to disrupt the normal stability that I have when viewing an object with a clear top and bottom. Similarly, the innocence suggested by the child's shoes does violence to my sense of normalcy when juxtaposed with the violence and sexuality of one of the incarnations of the dolls (Fig. 3). In its conflation of taboos - necrophilia, molestation, rape - Bellmer's dolls epitomize Surrealism's desire "to lay waste to the ideas of family, country, religion" (128).

For me, the dolls are not titillating, but anxiety-producing and disorienting. However, the confusion of sex and violence, innocence and sexuality, life and death presented by the strangely realistic dolls goes beyond mere shock value; the dolls also introduce a number of issues about the nature of violence. The idea that Bellmer found violence sexy but exercised his practice in art rather than in life suggests that art can be a release for spectators and artists of unthinkable or impossible urges. The dolls intrigue me for their implied sadomasochism, for the "dark" side that they represent. Moreover, the notion of erotic violence, particularly in the works of Freud and the Marquis de Sade, embed the dolls in a larger network of ideas regarding the human subconscious and desire. Since I value a work of art by its ability to stimulate and feed the imagination, I read the critical activity surrounding La Poupée as an index of the work's importance. In this sense, when Clayton Eshleman finds Nazi horrors in the image of La Poupée, he is giving evidence of the dolls to catalyze emotions in and horrify the viewer.

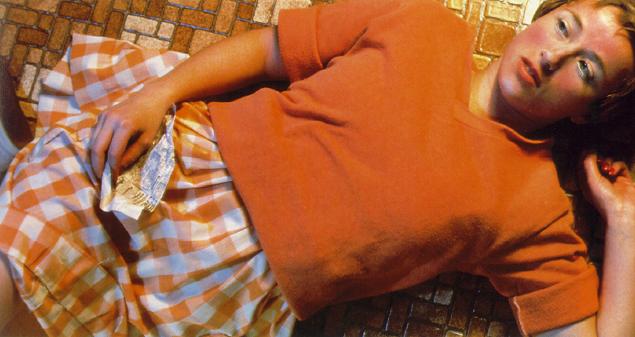

We find a different type of horror in many of Cindy Sherman's photographs, yet ones which are equally involving of the individual reader's response. In photograph #96 (Fig. 6, below), we see a youngish woman, played by Sherman herself (as always), lying on an orange tile floor and loosely holding a ripped section of telephone book or newspaper page. The woman, dressed in a girly skirt and sweater of sunny orange tones that are echoed in her blushed cheeks, looks off into the distance with a daydreaming, sad expression. The color of the tiles mirrors the sunny stripes of her dress. She may be a teenager.

Fig. 6. Cindy Sherman, Untitled #96, 1981.

Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Illus. 60 of Cindy Sherman, by Peter Schjeldahl (Mnchen: Schirmer/Mosel, 1987).

One of the tasks I take upon myself in reading this image is reading the woman. The recurrence of Cindy Sherman's face in her photographs tells me that, if nothing else, her works are partly about the representation of women. In this photo, without exterior characters or settings to tell us who she is, I pay more attention to her clothes and makeup. I notice that makeup is barely present, if at all. I wonder if the glow in her cheeks is delicate, natural makeup, or just the gentle flush of her face. In the sunny colors, cleanliness and youthful, 1950's styling of her sweater and skirt, I sense the presence of a young, sweet, possibly innocent girl or woman. The soft colors, young face, delicate posture and expressions, and stereotypically girlish clothing connote femininity. Upturned leg with white tennis shoe, neatly rolled up sleeve, blonde hair, and kitchen-floor surroundings reiterate that theme.

However, there are aspects of this image which jar me. As in many of Sherman's photographs, certain details lead me to rethink my conception of the image. As noted before, Sherman herself is the actor in all of her images. I am struck by the transformation of Sherman herself. In other photographs, Sherman has played an anxious housewife, a tense, aged woman, and a wealthy but somewhat sleazy lady of status; the recurrence of the same face behind an utterly different mask is unsettling. In addition, the very heavy-handedness of connotation -- the overly orange orange, the girlish, slightly distracted expression, the blush, the wholesome skirt -- suggest to me that something is not right. Just as I saw through the too-reasonable happiness of Doris Lessing's heroine, I feel that something is amiss in this overly orange picture of girlishness.

Other even more explicit details tempt my curiosity. The scene is replete with tiny details that lead me on, like a forensic detective, to imagine a scenario. First, I see the paper in her hand and read, barely, the word "SINGLE?" Is it a personal ad she is holding on to? Is it an important telephone number? Why is it crumpled? More importantly, why is she lying on the floor? The text of the photograph gives me room to imagine many different scenarios: possibly, she has called or is contemplating calling a personal ad. Her distracted expression and pose suggest that her innocence is in danger: Should she be calling this number? Are the thoughts of a woman lying on the floor healthy ones? Her very indecisiveness, suggested facially, is compounded by the single scrap of paper into loaded images of the woman's past or future. The possibility that she has fallen from grace or is about to is connoted by the disturbing excess of innocence in the present image.

We can see, then, that while Sherman's photograph provides many universally shared codes for producing meaning -- innocence and femininity are clearly enough defined in our culture's advertisements, book covers, religious depictions -- the most intriguing and important aspects of the photograph lie in the realm of the individual reader's imagination. Ambiguity and suggestions of a narrative encourage me to spend time trying to figure out what happened or is about to happen. The emphasis on the "before" and "after" obviates an active involvement of the reader's personal visions. What makes the photograph grab me are the images and conclusions born in my mind.

At the same time, I am intrigued by what Barthes' terms the punctum, that part of the image that "extends the life of the subject outside of the image, produces a more authentic effect of reality than the semiological mechanisms of literature" (Moriarty, 204). Like Barthes' punctum, the spark that produces such a response is often an enigmatic, unanalyzable detail of the image -- a look on the face, a turn of the hand. Each of these aspects is linked to the individual's experiences and habits. The phrase "SINGLE?" strikes a particular chord with me. I might feel that I know the woman as a character, whereas to another reader she might be completely foreign. The image of the checked skirt might spark a torrent of thoughts on skirts and feminine clothing in me, and remain an item in the abstract to another reader. I associate the tilework of the kitchen floor with suburbia and wealth. In the prostrate position of her body, I see the image of an abused woman, maybe someone who is recuperating from a shock; this notion is fed by remembrance of other Sherman images in which the woman is clearly dismayed.

Each of these readings are given life in the free, associative interaction of reader and text. Moreover, they are grounded in more widely shared perceptions: that the woman is innocent-looking; that her recent future or past is troubled; that the mysterious piece of paper and her position on the floor are somehow related. Again, I feel that my role as spectator is related to awkwardness. I move into a position of information-seeking by the very ambiguity of the image's text. I am troubled both because this woman is not happy, and because I don't know why. Cindy Sherman's photograph disrupts my desire to see something familiar, to see an image of happiness, or to at least know what has happened. However, this frustration, which activates my imagination, is the art of the photograph. By encouraging me, the spectator/detective, to look for something that is not readily apparent -- while denying the slick beauty most often provided in advertisement-images of women -- the photograph alerts me to conventions of looking.

It might be useful at this point to reexamine the paradox presented by an audience-oriented approach to art. The contradiction lies in that the reader has power to construct the text, yet a work has the power to point out certain truths. However, the contradiction can be reconciled. This ability of a work of art to accomplish something despite the infinite variety of meanings brought to bear by audiences is made possible by interaction between reader (infinitely variable) and text (static). Again, I see this as part of Eco's 'merest order': a work of art goes beyond mere noise because some responses and structures are shared, in vague forms, by many readers. Thus, the infinity of readers does not dissolve a work into meaninglessness, but allows there to be multiple texts generated by a work of art, some more basic and widely shared than others. In the works I have chosen to look at, these shared responses are given to the reader through narration and other clues. Within these loose strictures the readers are free to develop, in cooperation with the text, an infinity of more subtle meanings.

For example, in the visual works we have looked at, my responses are often guided by what I cannot see or do. Magritte's painting is limited by the inability of the reader to see the "whole" woman. This characteristic is the starting point for a set of responses that may diverge widely. Bellmer's dolls do not give us the stability we might expect of an image. The violence inscribed in La Poupée is a shared structure that allows individual responses -- indignation, fantasy, and fear -- to shape one's interpretation. In Sherman's photograph, a shared set of connotations -- innocence, femininity, impending narrative -- form the basis for an infinite set of potential readings.