Individuality in Readers of the Work of Art: The Reader and the Artist

See more academic essays

Part of what interests me in the preceding works is the notion of awkwardness and intrusion on the part of the reader. Browning's "My Last Duchess" intrigues me despite an uncomfortable feeling of voyeurism; I defile a sacred place, the secret concealment of the duchess, by my act of reading. Lessing's story engenders a similar process of discovery. The initial insistence on 'all being well' slowly gives way to realization of Susan Rawlings' depression, though I have misgivings before being explicitly told. "Lady Lazarus" has a more direct, confrontational approach to the theme of suicide. The dizzying array of emotions and horrific images in Plath's poem makes me at times uncomfortable; part of the process of reading entails becoming part of the sad, desperate performance.

On a similar note, the Surrealists had a flair for the theatrical; art was made to foment revolutions in thought and social habits. Consequently, Bellmer's dolls aim for sudden anxiety; I am distressed immediately by the images of torn, naked body parts. Magritte's painting has an ugliness that reminds me, in an instinctual, immediate way, of what representation does. Finally, a much more recent work, Cindy Sherman's Untitled #96 troubles me with images of fallen grace, and uncertain future. I break the photograph's surface of innocence with my own probings into the possible meanings of the image. I become an accomplice in the "unveiling" process.

These issues are extremely important guides in the treatment of spectators of my own work. Do I want to create a sense of intimacy with my images, as did Lessing, entangling the reader with claustrophobic closeness? Or do I want to shove readers away in violent confrontation, as did Bellmer? Anything satisfying at the onset too easily affirms existing values. I do not want to confirm already expected desires -- the desire to see something beautiful or easily understandable. I do not want to frighten the viewer into silence or anger, as Bellmer's dolls frequently did. Embarrassment as a creative response is ideally located between satisfying contemplation and violent confrontation. The embarrassed viewer is not in a state of shock, but is brought to unfamiliar ground. A sense of unfamiliarity is pervasive, and it is this self-consciousness that I find valuable.

My goal in painting is to capture the sort of awkwardness that is suggested by Cindy Sherman's photograph. I want there to be a slow anxiety, punctuated by a more threatening expression or detail. I am interested in confrontation as well; I want to have an aspect of theatricality, such as that in Plath's "Lady Lazarus," that transforms idle spectator into viewer, attentive watcher.

Before discussing the role of the reader in my own work, it is vital to ascertain the role of those elements of painting that are not present in literature. That is, I must investigate the nature of the physical presence of paint.

Color is a tool for deviating from representation. In Julia Kristeva's analysis of the color in Desire in Language, she notes that "by overflowing, softening, and dialecticizing lines, color emerges inevitably as the 'device' by which painting gets away from identification of objects and therefore from realism"(231). Rather than adhering to underlying structure or anatomy, color bleeds away; color is that undefinable mass that is merely surface, yet can suggest volume, and can disrupt our expectations of volume. In Kristeva's account of color, it is the symbol of Chaos, the first introduction of disorder into an otherwise primarily logical system of painting.

Color speaks to some other part of us than do icons. For Kristeva, the power of color as a force of Hell is its place below our analytical system; part of our response to color, beyond our intellectual control, is instinctual. We can say that colors are outside of language. Unlike images that may be described in endless words, colors have a finite set of descriptors: red, blue, and if we are fancy, magenta, fuchsia and the like. Yet, no one doubts that color is part of an infinite spectrum. Colors are as numerous as words, and can come together in an infinite variety, though there is no explicit system of what it means; there is no dictionary for color meanings, no lexicon of sense allowing us to read such changes in the light spectrum. At the same time, colors are a large part of what we must read when we look at paintings. Beyond the recognizable icons that can be given verbal equivalents and analyzed in verbal fashion (woman, skirt, sad face) we have to make something out of the colors.

That is not to say that colors are devoid of nameable, or at least associable, meanings. In Sherman's photograph, for instance, orange suggests femininity and innocence. There are many cultural texts suggesting what certain colors symbolize: purple for royalty, red for anger or lurid sexuality. However, the effects of color go far beyond even these loosely tagged meanings. Not every color is as connotative as the warm, sunny colors in Sherman's photograph, and not every dab of red means anger; nor does a notion like "anger" or "innocence" always gravitate toward particular colors. The artist must use colors, and therefore some color will provide meaning that we have no names for. Particularly in modern painting, color is often suggestive of pure color or light.

Color is part of a system that is more mobile, fluid, and "alogical" than nameable icons. We can see a similar process going on with texture. Rosalind Krauss, in her analysis of the sculpture of Rodin, notes that surface takes on a different role in his work. While classical and neoclassical sculpture were obsessed with underlying forces and mass, cause and effect, Rodin allowed the processes of the making to show forth in the surface of his forms, disrupting the "perfect" alignment of internal structure and external shape. Krauss explains this emphasis on surface, found in such works as "Je suis belle," as "an opacity between the gestures through which they surface into the world and the internal anatomical system by which those gestures would be 'explained'" (25-26).

In sum, color and texture serve as the prime tools by which painting and sculpture deviate from their more purely representational predecessors. For Kristeva, the surface of colors (and later, textures as well) is the averbal side of painting; literature lacks the noisy, nameless substance marked by color. Yet, language has a surface, too; language, especially in literature, is full of references, sounds, and double meanings that elude our search for a signified. I might even say that language is surface -- that the word-plays and displaced meanings of modern literature are more about surface than about interior structures.

In such poems as "Lady Lazarus" what is generated is not a coherent structure of meanings that point to an underlying core, but rather a multiplicity of signs, a layering of texts that refuses our efforts to see underneath. Phrases have meaning in relation to specific contexts of speaking, a constantly shifting notion dependent on readers' experiences. As Barthes notes, there often emerges a third meaning, one that hovers, indefinably, above the text (Image, Music, Text). The meaningfulness of connotation emerges as a haze above more precisely nameable meanings.

It is this haze, this noise that adds ambiguity to both verbal and visual texts, that I search for in my own work. It is with readers in mind, not the ideal reader but the possible reader, that I swim through the murky depths of ambiguity: I want to provide a work that involves all readers, while allowing one to grasp different meanings than another. Consider, for example, the paintings below.

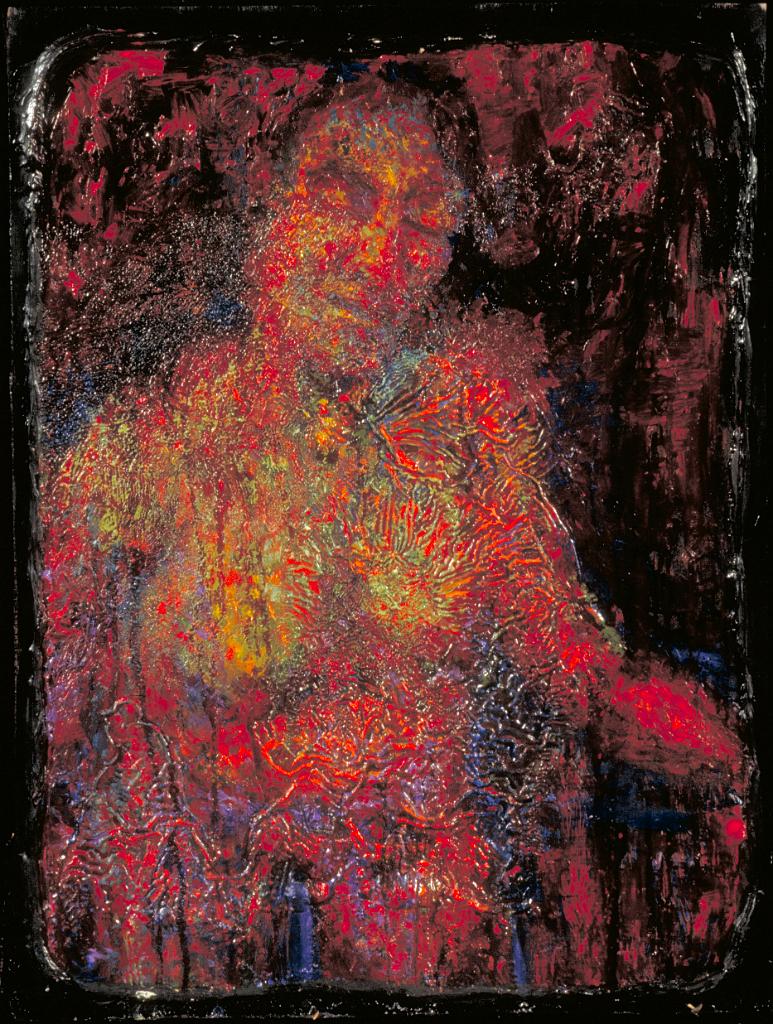

Fig. 7. Kristen Ankiewicz, Woman #1, Dec. 1992

Oil on canvas, 32 x 24 inches

In Woman #1, an older woman is leaning forward slightly, with her eyes closed and her head slightly tilted. Layers of paint were built up over time. Many of the layers were very wet, drying into drip patterns or sheets of thin material. A thicker, unpigmented oil (stand oil) was applied in other places, drying to a reticulated, veiny texture. I created the image of the female with loosely defined applications of color, intending for the whole to form her shape without painting the contours in directly. In this way, I hoped to have the figure "emerge" out of the layers, just as she emerges out of the representational frame/background of the painting.

Fig. 8. Kristen Ankiewicz, Woman #2, Dec. 1992.

Oil on glass, 19 x 31 inches

In Woman #2, I used the "reticulation technique" over the entire surface. Leaving very thick, unpigmented oil to dry for many months, I returned and painted thinner layers of paint over the veins and bubbles that formed from the first layer. Some of the bubbles enclose never-dried oil. As in Fig. 7, the woman is older, her eyes are closed, and she is facing outward from the painting. Her head is slightly tilted downward, her arms are positioned laterally and downward -- maybe as if to hold on to something (the frame of the painting, a walker), or to immerse them in water.

Fig. 9. Kristen Ankiewicz, Couple #1, Dec. 1992

Oil on wood, 24 x 32 inches

Fig. 9 continues a theme I had begun a year earlier, involving a a fat-faced man next to another character. The large, red-faced man looks out of the right side of the painting, while a smaller, red man (woman?) looks down, more introspectively, toward the left exterior. On the face, a veiny, pocked texture emerges from two or three layers of paint over a base layer of gesso (a hard, acrylic substance). The larger, older man has raised his eyebrows. His position indicates that he might be moving forward, or away from the other person. A green-orange mesh of layers comes down between them.

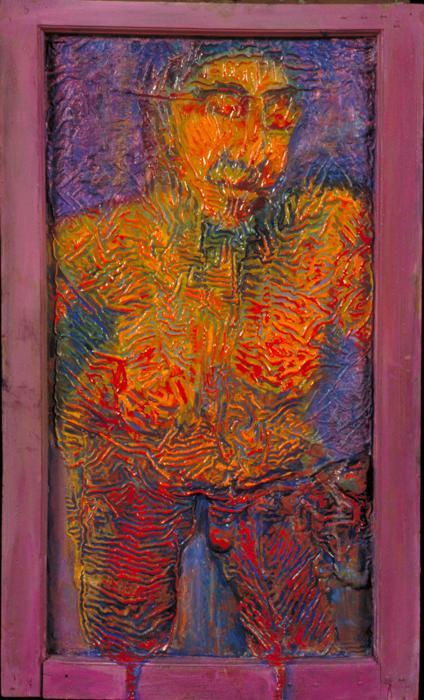

Fig. 10. Kristen Ankiewicz, Couple #2, Dec. 1992.

Oil on wood, 24 x 32 inches

Here again I juxtapose an outwardly-gazing man's face with a more distant, smaller body. The person (woman?) in the background, reminiscent of Woman #1, is partly immersed in a pool of water. This figure leans forward, as do both previous women; the face is somewhat masculine, the body stiff, possibly old. The breasts hang forward a bit as arms reach into water up to the elbows. The face is directed forward, bending upward from the body in the way one might hold one's head when trying to understand a tactile sensation, or listen to music.

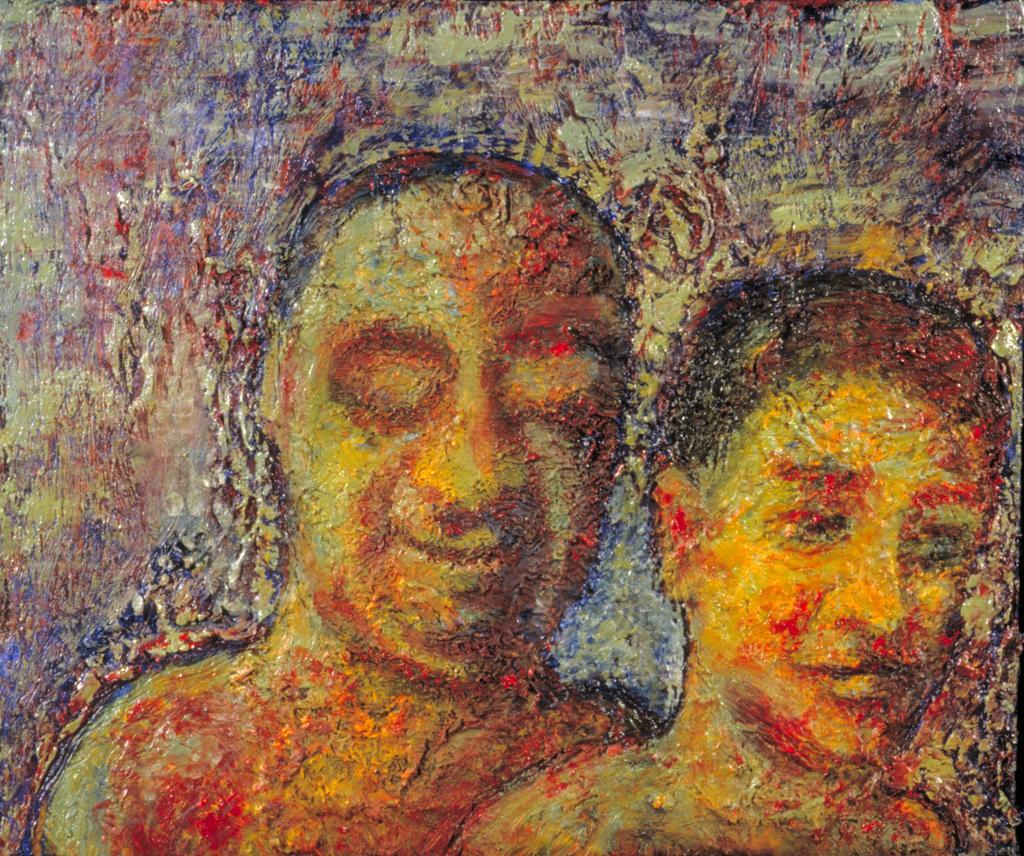

Fig. 11. Kristen Ankiewicz, Couple #3, Feb. 1993

Oil on canvas, 28 x 33 inches

Though these figures are probably the most clearly modeled and contoured, the paint layers are also the thickest. The two figures are closer to each other than in Figs. 7-10, but they are not facing each other. I also introduced an explicit smile in the face of man, who with his eyes closed could be fantasizing. The more frontal figure is leaning slightly downward to the right. I introduced open eyes for the first time to this character.

Fig. 12. Kristen Ankiewicz, Couple #4, March 1993

Oil on canvas, 35 x 36 inches

Here the couple, similar to the couple in Couple #1, is close to the "fourth wall" of the painting. As in Couple #1, the smaller figure has closed eyes and the large-faced man has open eyes. Only the faces and shoulders are visible, and there is little visible background. This painting is bigger than the others, as I wanted a more intimate perspective of the two people than before. The layering of the colors is applied so as to add ambiguity, with thinner, more fluid washes applied over a hard, scratched surface. The initial surface of gesso was scratched to form the portraits. The modeling of the forms is more ambiguous than in previous images, and the darker blues and browns form a more even distribution of tones.

In discussing these works, I face the difficulty of reading what I, in a sense, wrote. I am not a free spectator. I know what I was thinking; I am the privileged author, who is supposed to have the answer. It seems that I would have to step outside of myself to become a "fresh eye," an innocent spectator. Yet, the dichotomy between authorial intention and reader fall apart in my mind. I do not have to "step outside myself" to imagine being a reader, for I am already my own reader. I am many readers, as a multitude of voices in my mind criticize, laugh, or take pleasure from my own work in much the same way another spectator might.

Intrigued by the role that spoken words play in the poems by Plath and Browning, I am drawn to facial expression and gesture as the most loaded but least understood of communications. I am fascinated by faces, by a glance or a raised eyebrow pregnant with meaning. Imagining the impact that one single detail of expression would have in my vision of Browning's Duke as he declares his refusal "Never to stoop," I imagined the reverse: expression and gesture without speech. I wanted the raised eyebrow to be alternately sinister and playful, evil and innocent.

A second inclination that directed my work here is the role of suggested narrative. Both Cindy Sherman's painting and Browning's poem convey an enormous sense of drama and action with a mere snippet of image. Cindy Sherman's girl lays on the floor, clutching a piece of paper; in her expression, position, and clothing, I create an entire scenario, a drama of fallen grace, tortured girlhood, mocked conventions and broken habits of representation. The photo denies a certain sense of happiness for me, as does Browning's poem, but these strictures are slight: most of saga comes out of my own conclusions to the drama. In all of the works analyzed so far, the juicy details are concocted by our own imaginations.

I hoped to create the same effect in the Couple series through the juxtaposition of two characters. When there is one character, I accept the task of character assessment. When there are two, I see action. Moreover, I complicated the stories by presenting similar characters in other paintings. I began with old women (Figs. 7, 8). Each of them is slightly masculine. I imagine a woman bending over, asking for help, using a walker, or testing the water in a pool. Eventually, there appears a young boyish woman, reminiscent of the old one in posture (Fig. 9). She grows more feminine in some paintings (Fig. 12), more masculine in others (Fig. 11), while the "masculine" man metamorphoses as well (Figs. 9-12). His face changes shape, his neck grew, his jowls changed size.

I think of the paint as material that stiffens movement and clouds vision. I want people to see figures reappear, in a different age or mood and transformed in some indefinable way, in other paintings. I imagine a strange world peopled by androgynes, feminine men and masculine women, none of them really beautiful, though I hope the readers come to question their perception of ugliness and beauty. I imagine a certain kind of sexual tension: why is one character clearly masculine, while the other is not so?

At the risk of disappointing my present readers, I assert that I don't know what the story is. Furthermore, my experience making the painting, while forever haunting and altering my perception of the final product, prevent me from becoming ultimate judge of its meaning. The very time and moods I went through as I finished the paintings, the very struggle involved, insure that my authorial intention does not provide a single, consistent core to which the reader should strive. Despite my clear aims as I painted, the image means many things to me, as it probably does to the "less privileged" readers. The readers of this painting are given generous space for imagination: Iser's gaps are left for the filling. I want readers to make up stories.

Underlying all of my work is the notion of every work of art as a performance. As in Plath's "Lady Lazarus" or Browning's "My Last Duchess," characters look out directly from my paintings, and the reader looks in, becoming (I hope) part of the action, however conceived. In Fig. 9, the man looks right out at the spectator. He looks as if to say "Figure me out. Look what I've done, what I am." His direct address of the audience is a visual facsimile of the dramatic monologue. I aim for the same ambiguity and weight of expression that one would read into the most sparse of dramatic phrases, heard without recourse to visual aids.

Other tools that grant a painting something approaching theatricality are, of course, color and texture. Red glares out at spectators, who are in a sense probing an open wound in a sunny green field. Veins in the texture of the bodies convey the three-dimensional confrontation of theatre or sculpture while retaining the two-dimensional qualities that alone belong to paint. The imposition of interior form on exterior volume is an artifact of the physicality of paint; it does what it does regardless of one's attempt to rein it in.

Color, as Kristeva notes, is the painter's tool of rebellion; for me, texture is that too. Texture and color are ways of openly confronting the audience without having to "spell out" intended meanings. Yet, as a student painter, I am also concerned with issues of originality and worth. In the words of Umberto Eco, "the originality of an aesthetic discourse involves to some extent a rupture with (or a departure from) the linguistic system of probability, which serves to convey established meanings . . ." (98). In other words, audiences do not pay attention to something they feel they have seen before. Originality requires a perversion of tools; originality requires the disordering of the sensibilities that comes from unexpected uses of color or line. Eco reformulates the power that Kristeva assigns to color.

In this vein, accidents produced by the drying of the oil can serve both to open the work as well as to ruffle the expectations of the audience. I am horrified and fascinated by the oiliness of oil. I am interested in paint as a form of skin, out of which the artist both metaphorically and literally remakes humanity. I hope to lure the reader into the "forbidden" aspects of paint, so that the suggestiveness of paint's texture will color (so to speak) the gaps left open by composition and representation. That was my intent in creating works that ask to be touched.

As noted above, one's perception of color and texture are partly unconscious, instinctual. It is in these realms that I hope to trap (and free) the reader. Again, the individuality of the reader is crucial to the process. In Couple #1, I want the spectator to awkwardly jump between the man's face and the other figure's sadness; between these red images and the veiny, unnameable texture and all that it suggests; between memories that are triggered by the man's upturned eyebrow, and faces that came out of an unfamiliar photoalbum (my own). I want the spectator to imagine their own unfamiliar thoughts, feel their own new awkwardness; I intend my painting to be midwife for feelings on selfhood, gender, and representation born entirely in the minds of individual spectators. It is the awkwardness of self-consciousness that I am after.